by Dr.Harald Wiesendanger– Klartext updatet

What the leading media are hiding

Eating a low-salt diet is a matter of course for health-conscious people. This is because salt is said to increase the risk of kidney damage, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. Doctors give strict advice accordingly, and patients in hospitals, nursing homes, and care facilities have to put up with bland food. In reality, it is much easier and more dangerous to consume too little salt than too much. What’s more, not all salt is the same—it’s the quality that counts. A medical myth is costing millions their vitality.

“First salt, then the Grim Reaper”: This is the grim title of an article by a general practitioner in Heidelberg published on the information portal doccheck, as if the salt shaker were the tool of choice for the Grim Reaper. After all, it is “well known that excessive daily salt consumption is a significant risk factor for high blood pressure and thus also for the development of cardiovascular diseases, especially stroke.”

The doctor’s alarmism follows conventional wisdom. This originated from a few uncontrolled case reports from the early 20th century, which were hastily included in textbooks. Since then, it has proved virtually impossible to eradicate. It is reflected in the recommendation of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) to consume no more than 6 grams of salt per day, as well as in the upper limit of 5 grams advocated by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Yet the available studies have long given cause to question this dogma. As early as the middle of the last century, an evaluation of all research results available at the time showed that The evidence was by no means conclusive. (1) “Since sodium and chloride are practically the building blocks of the biochemical structure of mammals,” the authors commented at the time, “it is hardly surprising that eliminating these substances from the diet ultimately leads to undesirable or even catastrophic consequences.” And nothing changed after that: In 2018, a systematic review of nine high-quality studies found that there is still no solid evidence to clearly support a low-sodium diet.

Textbook wisdom refuted – the SODIUM-HF study

The large-scale SODIUM-HF study, whose results were published in April 2022, was intended to provide clarity. (2) It involved 806 adult patients at 26 sites in six countries. With an average age of 66, they suffered from chronic heart failure in stage II to III according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, i.e., with mild to severe limitations in exercise capacity but still symptom-free at rest. All of them were receiving guideline-compliant medication.

These subjects were divided into two groups of equal size: one group received only general advice on sodium intake in their diet, while the other was instructed to follow a strict low-sodium diet of no more than 1500 mg per day.

Cardiologists monitored the health effects of these guidelines for six years.

In the first year after the start of the study, the average sodium intake in the diet group fell from 2,286 mg per day to 1,658 mg, and in the control group from 2,119 to 2,073 mg.

How did this difference play out by the end of the six-year observation period? By then, 15% of the low-sodium group and 17% of the control group had been hospitalized for cardiovascular reasons, visited the emergency room, or died—a difference in incidence that was statistically insignificant. Surprisingly, the overall mortality rate in the diet group was slightly higher at 6% than in the control group at 4%.

And so the authors succinctly concluded: “In outpatients with heart failure, dietary intervention to reduce sodium intake did not result in a reduction in clinical events.”

What was the effect of this difference up to the end of the six-year observation period? By then, 15% of the low-sodium group and 17% of the control group had cardiovascular-related hospitalizations, attended the emergency department, or died—a difference in incidence that was statistically meaningless. Surprisingly, the total mortality in the diet group was even slightly higher at 6% than in the control group at 4%.

The authors concluded succinctly: “In ambulatory patients with heart failure, a dietary intervention to reduce sodium intake did not result in a reduction in clinical events.”

One shortcoming of the study may have skewed the results: the fact that the control group did not consume particularly high amounts of salt either. In this respect, the two groups differed by only 415 mg per day. An adult in Germany consumes an average of 8 to 10 grams of salt per day, while an American consumes 9.6 grams, meaning that the control group does not really represent a population that indulges in a typical Western (unhealthy) diet.

Another criticism is that the patients included in the study may not have been ill enough to benefit from a low-sodium diet. It is possible that a benefit would have been seen if patients with severe heart failure (stage IV) had also participated.

However, these shortcomings do not invalidate the results. In his analysis for the information portal Medscape, electrophysiologist Dr. John Mandrola states: “SODIUM-HF (…) has shown that in a typical heart failure cohort, recommending a stricter low-sodium diet makes no difference in treatment outcomes compared to general advice … My conclusion is that we don’t need to spend time and energy trying to get patients to follow an extremely low-sodium diet.”

Heidelberg nutritionist and preventive medicine specialist Dr. Gregor Dornschneider, who works in the therapy camps run by my foundation AUSWEGE, also gives the all-clear: “Around 80% of people with normal blood pressure – between 120/80 and 130/85 mmHg – are not salt-sensitive; This means that even if they consume more salt, their blood pressure remains unaffected. Even among so-called pre-hypertensive individuals – with “high normal” blood pressure readings of up to 140/90 mmHg – around 75% show little to no reaction to increased salt intake.” (3) Even among “manifest” hypertensive individuals – with permanently higher values than 140/90 mmHg – salt does not increase blood pressure in half of them.

A much bigger problem: salt deficiency

In reality, it is quite difficult to consume harmful amounts of sodium, but easy to consume too little. Doctors should therefore make every effort to inform their patients about the extreme dangers of an overly low-salt diet, rather than scaring them about salt. As an electrolyte—a substance that conducts electricity—sodium helps regulate the amount of water in and around cells, as well as blood pressure. People with low salt levels can become chronically dehydrated. Sodium levels below 115 nmol/l are considered critical. This leads to increased water displacement into the cells, causing various organs to malfunction—such as kidney failure—and the risk of brain swelling, which can lead to impaired consciousness, convulsions, and even coma. A sodium level below 110 mmol/l that is not corrected immediately can be fatal. A study conducted in 181 countries found that life expectancy is lower in countries where less salt is consumed. Even mild hyponatremia—a sodium level that is too low—significantly increases the risk of death. (4)

Far from being life-threatening, a prolonged salt deficiency caused by a low-sodium diet can lead to a host of persistent symptoms that can greatly impair quality of life. These range from fatigue and insomnia to nausea and vomiting, headaches and muscle pain to erectile dysfunction, concentration problems, and confusion.

The fact that too little salt increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes was proven in 2014 by the PURE study involving around 102,000 participants from 19 countries. Further studies have confirmed this. Thomas Lüscher, head of the Center for Molecular Cardiology at the University Hospital of Zurich, believes that this is because when salt intake is very low, the body releases hormones that raise blood pressure. “It’s similar to blood sugar in diabetics,” he explains, “too much is dangerous, but too little is also dangerous.” (5)

Our blood pressure does indeed drop when we drastically reduce our salt intake – but usually by less than 1%. Unfortunately, this worsens the ratio of total cholesterol to “good,” protective high-density lipoprotein (HDL), which is a much more reliable predictor of heart disease than “bad,” vessel-damaging low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Triglyceride and insulin levels are also elevated. Thus, the risk of heart disease is more likely to increase than decrease, even if blood pressure readings appear to improve.

Worse still, salt deficiency also increases the risk of developing insulin resistance, as the body conserves salt by, among other things, increasing insulin levels. Higher insulin levels help the kidneys retain more salt.

Insulin resistance, in turn, is a characteristic not only of heart disease but of most chronic diseases.

Our salt status also has a direct impact on our magnesium and calcium levels. If we don’t consume enough salt, our body not only starts to extract sodium from the skeleton, it also removes magnesium and calcium from the bones to maintain normal sodium levels. To the same end, it reduces the amount of sodium lost through sweat, excreting magnesium and calcium instead. In addition, low sodium levels increase aldosterone, a sodium-binding hormone that also reduces magnesium by ensuring that this vital mineral is excreted in the urine.

A strictly low-sodium diet is therefore one of the worst things we can do for our health — especially for the condition of our bones and heart.

Many patients with high blood pressure are prescribed diuretics: water pills that make the situation even worse.

Also, consider coffee consumption. Recommendations for low salt intake rarely take coffee consumption into account, even though drinking coffee quickly depletes salt stores. If you drink four cups of coffee a day, you can easily excrete more than 1 teaspoon of salt in your urine within four hours. Nevertheless, doctors advise them to consume no more than 1 teaspoon of salt per day. This corresponds to approximately 2,300 mg of sodium. Coffee drinkers who follow this advice can suffer a significant sodium deficiency within a few days, as their bodies lose large amounts of salt.

Coffee drinkers are even more at risk if they engage in intensive sports, regularly visit the sauna, or perform physically demanding activities. This is because the body also excretes sodium through sweat: 700 to 2000 mg per liter. So if you sweat a lot, you may lose more salt than you consume on a low-salt diet.

Required reading for all salt phobics in white coats

Salt intake used to be ten times higher

From a historical and intercultural perspective, the general recommendation to limit salt intake does not make much sense, as cardiologist James DiNicolantonio from Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City explains in a book that is well worth reading. (6) In reality, people consumed significantly more salt than we do today for thousands of years – but in meals that consisted exclusively of what nature provided, without artificial additives. Our ancestors only adhered to the WHO recommendation – a maximum of 5 g per day – in the earliest stages of human history, during the Stone Age, which began around 2.5 million years ago and ended between 3000 and 2000 BC, depending on the region. The daily salt consumption of hunters and gatherers at that time is estimated at half to one gram, obtained exclusively from natural foods such as meat, blood, and plants.

In ancient times, salt became the most important preservative and remained so for two millennia. Soldiers were partly paid in salt – hence the word “salary.” The ancient Romans consumed 7 to 12 grams per day.

In the Middle Ages and well into the 19th century, it was already twice as much, at least in Europe. (7) Daily salt intake rose to 15 to 30 grams because meat, fish, and cheese were cured, smoked, and salted. This is three times more than the 8 to 10 grams that Germans consume per day today, according to the DGE. (It was not until 1876 that Carl von Linde invented the first industrially usable refrigeration machine – which revolutionized cold stores, breweries, and the meat industry – and in 1913 Fred Wolf followed with the first electric refrigerator for domestic use. The frontrunner, a typical 16th-century Swede, is estimated to have consumed an average of 100 grams of salt per day. But did this result in a significant increase in high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, strokes, kidney failure, osteoporosis, stomach cancer, edema, autoimmune diseases, and dementia?

The Chinese and Japanese, who have some of the highest life expectancies in the world, also consume the highest amounts of salt: an average of 13.4 and 11.7 grams per day, respectively.

Why do salt alarmists ignore the fact that hospital patients routinely receive large amounts of 0.9% sodium chloride solution intravenously? They often receive ten times the recommended daily intake of sodium chloride – yet their blood pressure often hardly rises.

At this point, at the latest, it should become clear to anyone with half a brain that there is something seriously wrong with the smear campaign against salt.

The fixed idea that salt intake correlates with blood pressure gained popularity with the publication of the DASH study (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) in 1999. The DASH diet does indeed restrict salt intake, but it also limits the consumption of sugary and processed foods, which can have a far greater impact on blood pressure than salt.

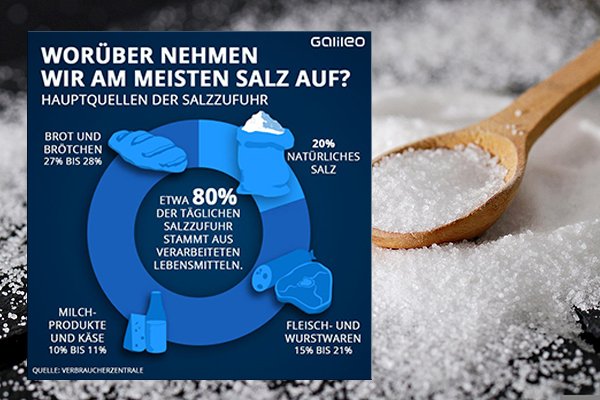

So perhaps it is not so much salt that is the problem in the prevailing Western diet, but rather the quality of the salty foods we eat – especially when they are industrial products. Per 100 grams, pretzel sticks and chips contain 2.5 to 4 g of salt, processed cheese and instant soups contain 3 to 5 g, sausage products contain 2.5 to 4.5 g – with salami at the upper end – ready-made sauces contain up to 15 g, and bouillon cubes and bouillon powder contain as much as 60 g. The average German consumer now gets most of their salt (75 to 90%) from processed foods. Yes, these products make us ill in the long term. But is this because of their salt content – or rather because of everything else we consume along with them? They contain too much sugar, too many inferior saturated fats, too many calories, too many preservatives, colorings, and flavorings, emulsifiers, stabilizers, modified starches, and other technically modified ingredients—but too few vitamins, minerals, fiber, and secondary plant substances. Such an unbalanced diet promotes obesity – and this is the main factor responsible for cardiovascular disease.

The salt debate is fatally distracting us from this real health scandal.

Primary sources of salt intake

About 80% of your daily salt intake comes from processed foods.

Galileo graphic: https://cms-api.galileo.tv/app/uploads/2020/05/grafik_salz.png Here, industrial pseudo-salt also appears to be included in the category “natural salt” – one would expect a little more differentiation from a science magazine.

Let’s listen to our bodies rather than questionable experts

In short, there is no serious reason to worry about too much salt in your diet. As a study from 2017 confirms (8), a healthy body always maintains a relatively constant sodium balance, regardless of how much it consumes. Healthy kidneys are easily able to excrete excess salt and keep blood pressure stable. According to DiNicolantonio, a person with healthy kidneys can consume at least 86 grams of salt per day.

In addition, our body has a built-in “salt thermostat” that tells us how much we need by regulating our cravings for salty foods. If we consume too much salt, we become thirsty and drink water, which dilutes the blood sufficiently to maintain the correct sodium concentration. So let’s learn to listen to our bodies. And remember that when we sweat heavily and drink a lot of coffee, we automatically need more salt than usual.

Much more important: the sodium-potassium ratio

While salt continues to be demonized as a cause of high blood pressure and heart disease, research shows that the real key to normalizing blood pressure is the ratio of sodium to potassium—not sodium intake alone. (7)

Like salt, potassium is an electrolyte. But while potassium is mostly found inside cells, sodium is mostly found outside them. Potassium ensures that our artery walls relax, our muscles do not cramp, and our blood pressure drops. (8)

As a rule of thumb, we should consume five times more potassium than sodium. Those who prefer a standard Western diet with processed foods probably consume twice as much sodium as potassium.

Research findings cited by the doccheck author quoted at the beginning of this article, on which she bases her grim predictions, demonstrate how fatal such poor nutrition can be. She refers to a study published in the European Heart Journal in early August 2022, which included health data from 501,379 people. At the beginning of the study, the participants stated, among other things, whether and how often they added salt to ready-made meals at the table – an approximate measure of their individual preference for salty-tasting foods and their usual salt intake. More than half, 277,931, reported never or very rarely adding salt; another 140,618 people said they did so “sometimes,” 58,399 “usually,” and 24,431 “always.”

At the end of the nine-year study period, there had been 18,474 deaths among the participants. Occasional salters had a mortality rate slightly above average, while regular salters had an enormous 28% increase in mortality risk.

However, Team Salt Phobia overlooks a crucial aspect of this study: Regular consumption of fruit and vegetables negated the significant statistical correlation between adding salt and mortality. Why? Because fruit and vegetables are rich in potassium. (Bananas and apricots are particularly rich sources, as are carrots, avocados, tomatoes, kohlrabi, potatoes, Brussels sprouts, peppers, and mushrooms. Nuts, dark chocolate, and certain types of flour are also good sources of potassium.) The conclusion: heavy use of the salt shaker is primarily harmful to those who do not value a healthy, wholesome diet.

Follow the money – down a blind alley

How could conventional medicine have been so persistent in pursuing such a misguided course? Follow the money: it wants to make money. Scaring everyone about salt is “a cornerstone of the blood pressure market,” says a US doctor critical of the system, who wants to continue practicing unmolested and therefore hides behind the pen name “A Midwestern Doctor.”

How so?

By declaring salt to be the main culprit for high blood pressure, a seemingly clear and simple risk factor is identified. This creates fear – even in healthy people – and promotes: a willingness to take “preventive measures,” not in the sense of genuine prevention, but rather checking certain measurements; consequently, regular blood pressure checks; the prescription of medication even for slightly elevated values; increased health monitoring with regular check-ups.

Hypertension, real or perceived, is a billion-dollar business – it generates global annual sales of around $25 billion for the pharmaceutical industry. Blood pressure medications such as ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, diuretics, and sartans are among the best-selling drugs. Treatment is long-term and permanently lucrative. If many people can be persuaded that their blood pressure “needs treatment,” a huge market is created for pharmaceutical companies. And the more people you scare into prevention and therapy with fear— “Salt is dangerous!”—the more this market grows.

As everywhere else in our profit-driven healthcare system, the prevention business thrives on fear marketing: salt = risk = disease = treatment. This logic follows a typical pattern:

– Define a ubiquitous behavior such as “salt consumption” as problematic.

– Emphasize potential dangers – dramatize the risk of high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke.

– Create uncertainty through alarmist media reports and brainwashed doctors.

– Offer solutions: early diagnosis (“pre-hypertension”) based on lower thresholds; early treatment with pharmaceutical products.

This is how a natural mineral becomes a medical-economic lever: salt is made a scapegoat to justify a lucrative long-term medical subscription.

Nutritional myths laid to rest

As always in life, it is important to find a middle ground when it comes to salt: between demonization and excess. It can help to remember the gap between aspiration and reality that has always been inherent in modern, supposedly scientifically rock-solid nutritional research. What food preferences has it not already exposed as unhealthy, even life-threatening? How often has it preached senseless, often even counterproductive renunciation of good taste? Mostly just for a limited time—until it became clear that eggs, for example, do not necessarily raise cholesterol levels and thus cause arteriosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, or that a vegan diet does not necessarily mean malnutrition. Other nutritional myths that have now been consigned to the graveyard include: “Fat makes you fat,” “Five meals a day are ideal,” “Breakfast is the most important meal of the day,” “Sugar is only problematic because of the calories,” “Light products help you lose weight,” “All calories are the same,” “Milk is a must for strong bones,” “Gluten is only relevant for people with celiac disease.” Much of the advice on “proper” nutrition “falls under the heading of religious freedom,” says Prof. Volker Schusdziara of the Technical University of Munich. “These are beliefs that everyone is entitled to have. But they are not medically or scientifically substantiated.”

Unfortunately, ascetic rules are similar to rumors and genetically modified organisms: once they are out in the world, they are almost as difficult to recapture as Aladdin’s genie from the bottle.

In the debate about salt, both sides are guilty of tunnel vision. We should not focus solely on this, warns Joachim Hoyer, nephrologist at Marburg University Hospital. “It is much better documented that obesity, smoking, and too little physical activity increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Instead of laboriously refraining from adding salt, we should perhaps get out into the fresh air more often.” Gregor Dornschneider makes it clear: “The far greater enemy of our health is a completely different crystalline product, namely industrially produced white table sugar.”

Not all salt is the same

Incidentally, not all salt is the same – it’s the quality that counts. To reap its physiological benefits, we should make sure that it is unrefined and as unprocessed as possible. This is true, for example, of pink Himalayan salt, which is rich in naturally occurring trace elements that are necessary for healthy bones, fluid balance, and overall health. Other good choices include other raw rock salts, natural sea salts, crystal salts, and the exquisite Fleur de Sel.

On the other hand, we should steer clear of cheap, industrially produced table salt for several reasons. It consists of up to 99.9% sodium chloride – valuable micronutrients that our body cannot produce itself are completely washed out. In addition, there are artificially produced chemicals such as moisture absorbers and anti-caking agents, including aluminum oxide. Cooking salt for sausage products also contains cancer-promoting sodium nitrite. Even small amounts of synthetic iodine and fluoride may be added – even though we could meet our needs for these trace elements in healthier ways elsewhere. In addition, around 90% of table salt is contaminated with microplastics. What’s more, industrial processing also radically alters the chemical structure of salt. What remains is “a dead seasoning,” criticizes Gregor Dornschneider.

Natural salt, on the other hand, usually contains 84% NaCl and 16% naturally occurring minerals such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and sulfur. These contribute significantly to maintaining a balanced acid-base ratio and ensuring proper nerve and muscle cell function. Salt is also essential for transporting nutrients in the body, absorbing them into cells, and removing waste products.

In addition, valuable trace elements in salt—including selenium, iron, zinc, silicon, copper, manganese, and vanadium—perform a variety of tasks in numerous metabolic processes: from protecting cells against oxidative stress and energy production in mitochondria to wound healing, blood formation, hormone regulation, and tissue development. (However, a balanced diet containing whole grains, nuts, seeds, legumes, vegetables, fish, and meat provides significantly more of these substances than natural salt does.)

Many people are amazed at how dramatically their health improves as soon as they start consuming healthy salts. Suddenly, they feel more energetic and mentally clear. Only now do they realize that behind the fight against salt lies a medical myth that is costing millions their vitality.

Long story short: for optimal health, we absolutely need salt—but not just any salt. What our bodies need is natural, unrefined salt without added chemicals.

However, it will probably be a while before the Grim Reaper comes for the last salt-free dogmatists.

See > Microplastics In Us: A Time Bomb

Remark

(1) Justin A. Ezekovitz u.a..: Reduction of dietary sodium to less than 100 mmol in heart failure (SODIUM-HF): an international, open-label, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet, 2.4.2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00359-5)

(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3041211/; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3064042/

(3) Zit. nach https://www.spiegel.de/gesundheit/diagnose/ernaehrung-schadet-zu-viel-salz-im-essen-wirklich-a-1020274.html

(4) James DiNicolantonio: The Salt Fix: Why the Experts Got It All Wrong – and How Eating More Might Save Your Life, New York 2017

(5) Cardiology Review September-October 1999; 7(5): 284-288, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11208239/. Weitere Studien, die für eine Reduzierung der Salzzufuhr zur Vorbeugung von Bluthochdruck zu sprechen scheinen, werden hier zusammengefasst.

(6) Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017;127(5):1944–1959, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI88532; New York Times May 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/08/health/salt-health-effects.html

(7) Advances in Nutrition, 2014; 5:712, http://advances.nutrition.org/content/5/6/712.full

(8) Harvard Health Publications, January 23, 2017, http://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/potassium-lowers-blood-pressure; Journal of the American Medical Association 1997;277(20):1624, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9168293; Journal of Human Hypertension 2003; 17(7):471, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12821954; British Medical Journal 2013; 346:f1378, http://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f1378

(9) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29507099/, summarized hier

(10) Zit. nach https://www.spiegel.de/gesundheit/diagnose/ernaehrung-schadet-zu-viel-salz-im-essen-wirklich-a-1020274.html

Quelle Galileo-Grafik: https://cms-api.galileo.tv/app/uploads/2020/05/grafik_salz.png