by Dr.Harald Wiesendanger– Klartext

What the mainstream media is hiding

Plastic is omnipresent, almost indestructible – and dangerous if it gets into our bodies. While the industry is trying to calm down, health authorities and legislators hesitate. Scientists have long been sounding the alarm: Tiny fibers and fragments of plastic that we unknowingly ingest through drinking water and food, the air we breathe, and our skin can cause chronic illness.

In the middle of the Christmas business in 2017, the chocolate manufacturer Feodora had to recall its popular “Anthon Berg” pralines: It cannot be ruled out that plastic parts got into the packages, the company said. The products should not be consumed under any circumstances.

Affected customers could return them. They were refunded the price, even without a receipt.

The logic behind this is ridiculous. It would immediately ruin our entire food industry if you thought it through because plastic has been everywhere for a long time: not only in water, in the rain, in the atmosphere, but also in drinking water, in the food chain, in our food, and thus also in our bodies.

It’s the price we’re belatedly paying for thoughtlessly turbo-charged entry into the convenient plastic age. The Belgian chemist Leo H. Bakeland opened the floodgates for him when he developed Bakelite between 1905 and 1907, the first fully synthetic substance made from petroleum. In the mid-1950s, our planet produced around 1.5 million tons of plastic a year – now we’re at approximately 280 million tons; a quarter of this comes from Europe, with Germany as the export leader.

In the meantime, the production volume would be sufficient to pack the entire globe six times. 8.3 billion tons of plastic have been put into the world so far – that corresponds to the weight of 822,000 Eiffel Towers, 25,000 Empire State Buildings, 80 million blue whales, or a billion elephants, as US researchers calculated.

Only a tenth is recycled, twelve percent incinerated; the overwhelming remainder hangs around in our environment or landfills. Recycling mainly just delays the point at which the material ultimately becomes waste. And so, the mountain of plastic waste will grow to twelve billion tons by the middle of the century if nobody takes countermeasures.

Pausing, braking, turning back: At least for the manufacturers, that’s the last thing they want to do. Because plastic is big business: the plastics manufacturing and processing industry make 800 billion euros in sales a year – around 60 billion in Germany alone – for which it uses four percent of the oil reserves.

Hardly any material is more treacherous, hardly any more stubborn. Because plastic is as good as indestructible, it does not biodegrade but, at best, breaks into smaller and smaller pieces. Micro waste can now be found everywhere – around us, inside us.

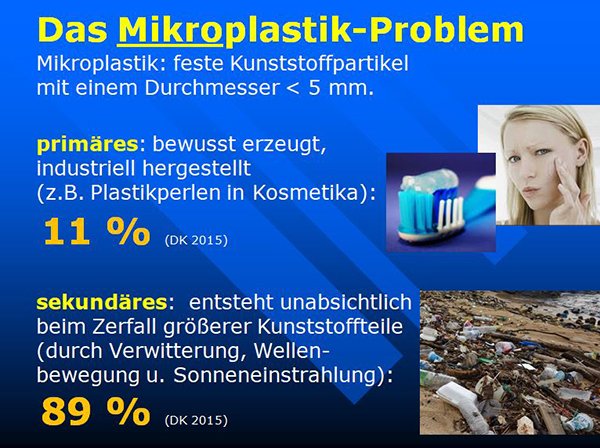

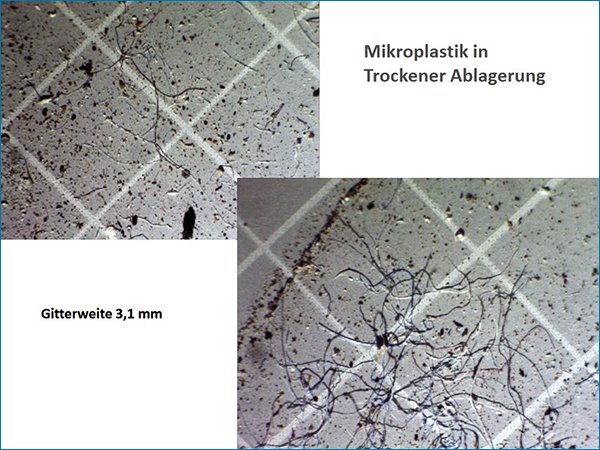

Hardly anyone gets upset about this because the parts are tiny, invisible to the naked eye, and can only be detected under a microscope. Some are only a few nanometers in size – thousandths of a thousandth of a millimeter.

The sources of the contamination

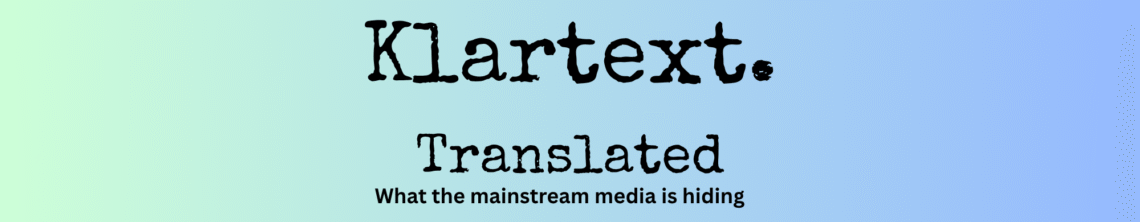

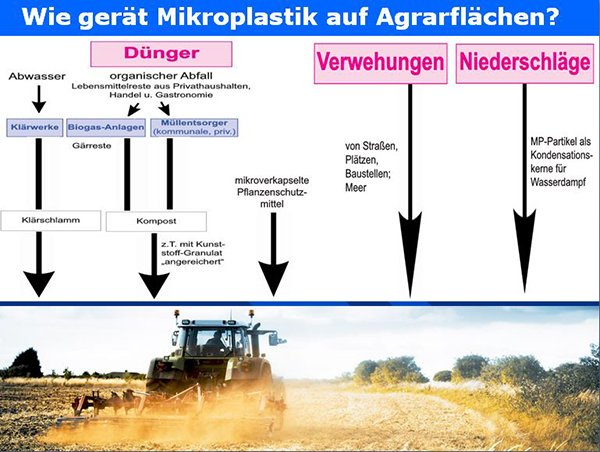

How does this stuff get into our living environment, into our organism? The sources are diverse. Experts distinguish between “secondary” microplastics, which result from decay and degradation, from “primary” produced so tiny from the outset.

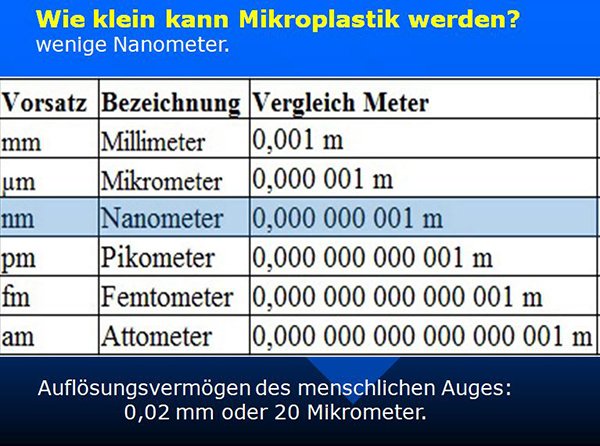

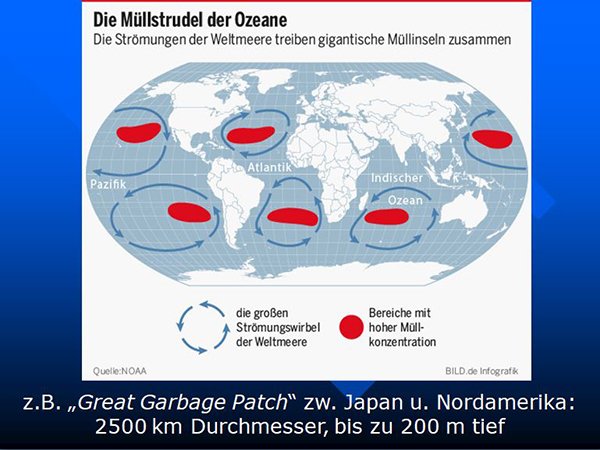

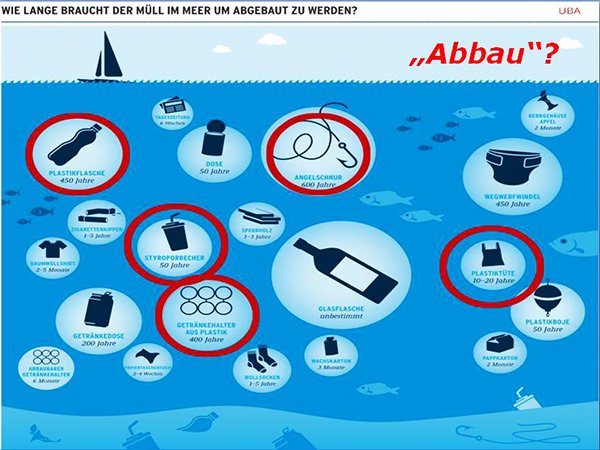

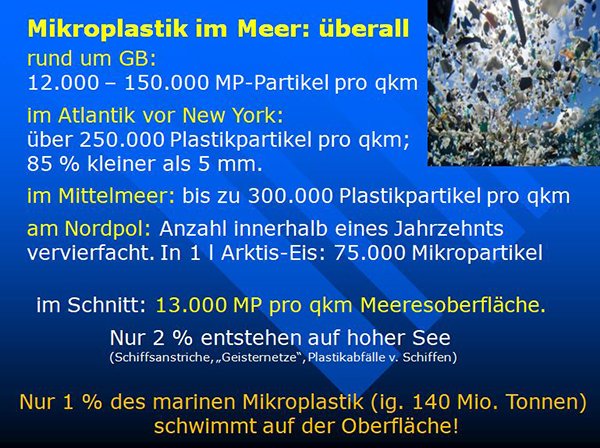

- The Federal Environment Agency estimates that up to ten million tons of plastic end up in the sea every year. THEY ARE PROBABLY THE MOST SUPERFLUOUS CONSUMER GOODS from PET bottles and shopping bags to straws. Over a billion of these rather childish intake aids are used worldwide daily. In the meantime, kilometer-long eddies of waste are swirling in all oceans, consisting primarily of plastic waste. In the Pacific between Japan and North America, the “Great Garbage Patch” drifts, a gigantic garbage dump full of plastic residues, 2500 km in diameter and up to 200 meters deep. Even around the North Pole, the amount of garbage has quadrupled in a decade. Waves and wind smash and crush the larger parts. Covered by crust, they sink deeper (“biofouling”). Or the sea current washes them onto the coast. Only over the course of decades, if not centuries, do the “nanofragment” break down into microscopically small fragments; It takes 400 to a thousand years before they have decomposed mainly. The pieces that a single one-liter plastic container can break into would cover a distance of 1.6 kilometers. Tens of thousands of pieces of plastic waste are now floating in every square kilometer; if it could be extracted in total, it would fill 38,500 trucks. It will increase tenfold by 2050 if things continue unabated. Fish, crabs, mussels, and other sea creatures eat the mini particles. If they end up on our plates, we inevitably eat them with them.

- Chemical leaks from plastic cutlery, drinking cups, containers, freezer bags, cling film, microwave dishes, bowls, cans, canisters, and many other everyday items. Germans use 320,000 single-use cups per hour, with a thin layer of plastic on the inside.

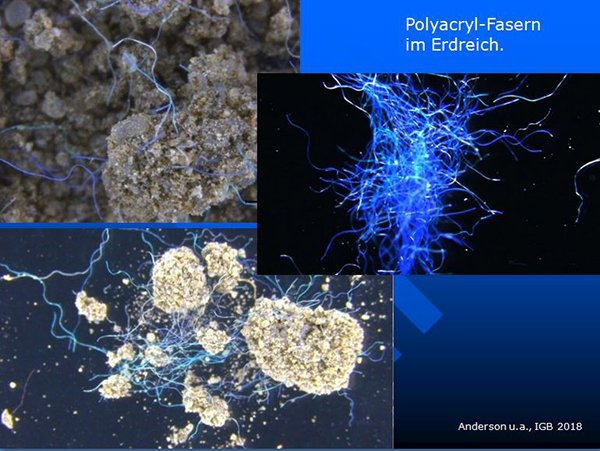

- Laundry. Washing machines start up around 36 billion times a year in Europe. A fleece jacket – often made from recycled plastic bottles – loses an average of 1900 synthetic fibers in a single wash. According to the environmental organization WWF, The EU-funded project MERMAIDS Life+, launched in 2014, even assumes that a million microplastic particles were released, 300,000 for an acrylic scarf and 136,000 for nylon socks. An estimated one million tons of plastic debris get into the sewage system into sewage treatment plants, rivers, and seas every year.

- The air vents of tumble dryers also blow synthetic fibers into the air.

- Countless microfibers are shed from carpets and upholstered furniture – especially when we beat them out – and from clothes, while we wear them.

- Colors. The fashionable latex and acrylic paints are essentially liquid plastic to which pigments have been added. When washing the brushes, it gets into the sewage system.

- Car tire. Approximately two billion are produced worldwide every year. Tens of thousands of tons of synthetic rubber are left behind on the roads every year as abrasion. Rain washes it down drains and streams, the lightest particles swirling into the air.

- Detergents, be it for cleaning machines or floor care.

- Personal care products. Microbeads, which are supposed to cause mechanical abrasion in toothpaste and liquid soaps, shower gels and shampoos, skin peelings, and face creams, are abrasive and scouring. We flush them into the sewage at the sink, shower, and bathtub; over eight trillion in 2015 in the United States alone. In some products, the proportion of plastic beads in the total content is close to ten percent.

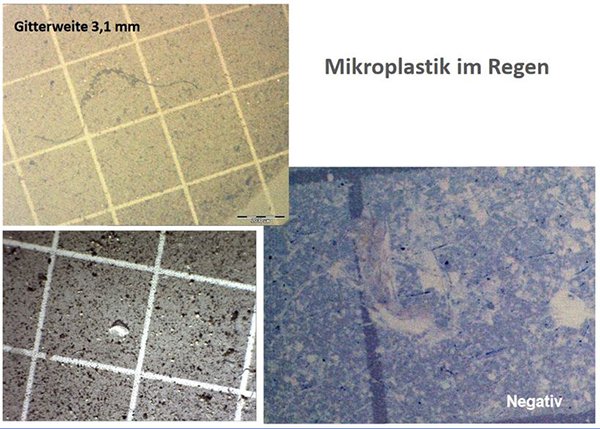

- Once in the sewage, microplastics migrate through the sewage system to sewage treatment plants, which can only partially filter it out. According to expert estimates, the rest, 10 to 30 percent, remains in the sewage sludge, of which 40 percent is spread on fields in Germany. The wind picks up the light fibers from dry soil and blows them away over a large area, as it does from air-dried laundry.

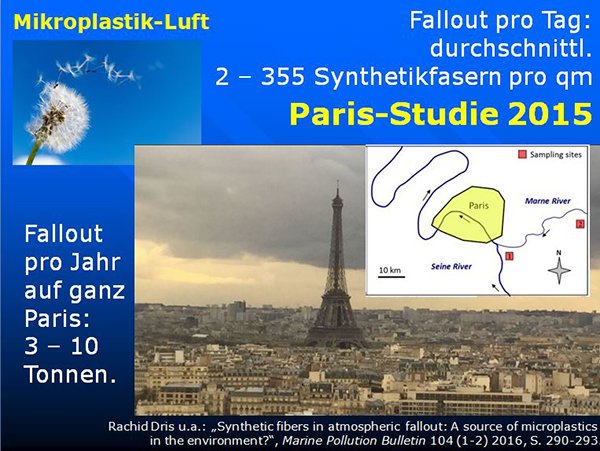

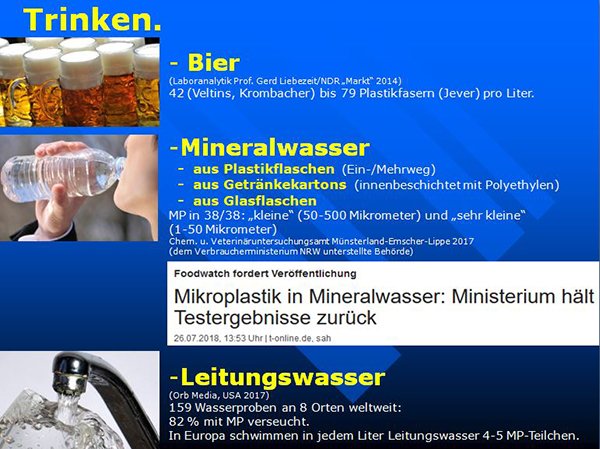

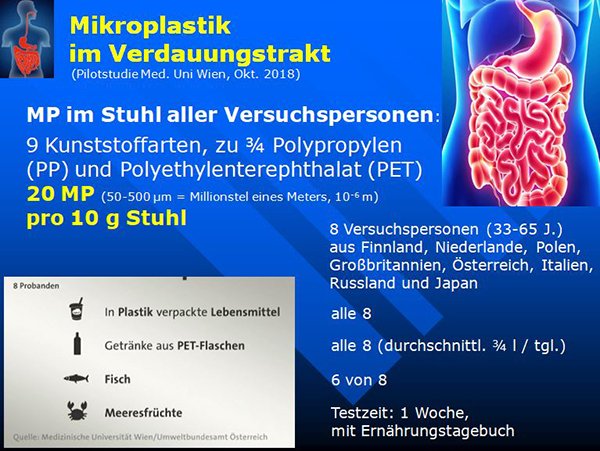

Microplastics sneak into our bodies through the air we breathe, drinking water, and food. In a ten-month study across five continents, scientists commissioned by the US media company Orb found microplastic fibers in four out of five samples taken from tap water at 159 locations. In Europe, it was 72%, in the USA even 94%. Developing and emerging countries are no less affected than industrialized countries: from Quito, Ecuador (75%) and Jakarta, Indonesia (76%) to Kampala, Uganda (81%) and New Delhi, India (82%) to Beirut, Lebanon ( 94%). The German researcher Gerd Liebezeit, emeritus professor at the Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Sea at the University of Oldenburg, discovered microplastics in numerous foods that he scrutinized. Plastic fibers and fragments even appeared in 19 honey samples; probably, the wind drove them to flowers where bees collected them. Researchers also found what they were looking for in Germany’s most popular types of beer: they found between 42 and 79 microparticles per liter. Two out of three shrimp from the North Sea are contaminated with microplastics.

The bad guys are lurking everywhere.

Almost every month, the free market economy extends the list of culprits with unbridled innovation. Particularly common are:

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC): It is found in food packaging, plastic films, cosmetics, bumpers in children’s beds, pacifiers, toys, floor tiles, shower curtains, seat covers, etc.

Phthalates (DEHP, DINP, and others): They are found as plasticizers in clothing, emulsion and printing inks, footwear, toys, food packaging, blood bags, breathing masks, and other medical devices.

Polycarbonates, most commonly with Bisphenol A as an ingredient: Are included under others in drinking bottles; in CDs, DVDs, and Blu-ray Discs; in glasses and Contact lenses; in the glazing of conservatories and greenhouses; in protective helmets; in camping dishes; in disposable medical products.

Polystyrene (PS) with styrene: It is hidden in food containers for sausage, fish, cheese, and yogurt, among other things; in the packaging of nuts and chips; in drinking cups,

crockery and cutlery; into toys.

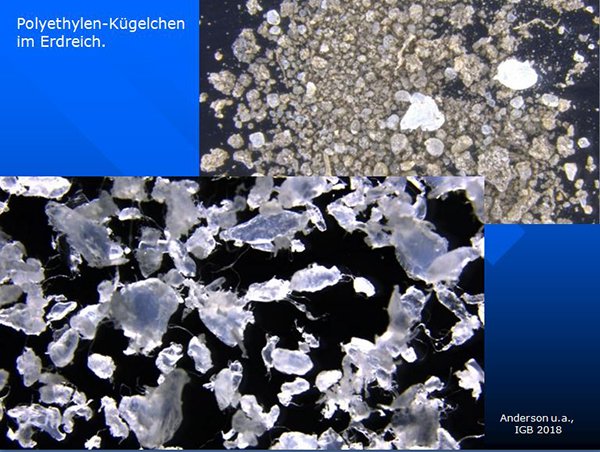

Polyethylene (PE): By far the most widely used plastic globally, primarily used in packaging such as cling film, carrier bags, milk carton liners, and garbage bags.

Polypropylene (PP): The second most commonly used plastic is often used for packaging, but also for fittings, child seats, bicycle helmets, wire, and cable sheathing, for pipes. PP fibers can be found in the home and sports textiles, carpets, medical and hygiene products; cups, bottle caps, dishwashers, warming containers, drinking straws, adhesive foils, and even banknotes in some countries.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is found in beverage bottles, carpet fibers, chewing gum, coffee makers, food containers, plastic bags, and toys.

Polyester: It lurks in bedding, clothing, diapers, food packaging, tampons, seat covers, etc.

Formaldehyde (methanal): It is found in paints, chipboard, plywood, insulating boards, flooring, and furniture. In addition, it is used for textile finishing (“crease-free”); for dyes and medicines; as a preservative in cosmetics; in vaccines to inactivate vaccine viruses or bacterial toxins; as a binder; as an additive in disinfectants, as well as in adhesives, fertilizers, tanning agents, casting resins, fungicides.

Polyurethanes: They are used as foams in pillows, mattresses, and upholstery; for insulation, thermal insulation, and flame retardancy; in paints and coatings; for textile fibers; for footballs and bowling balls; for rubber boots, condoms, shoe soles, and standing mats, in imitation leather, in color cosmetics, sun protection, skin and hair care products.

Acrylic: It is found in paints, varnishes, and glues; in the dental field, it serves as a Material.

Tetrafluoroethylene (TFE): It hides in irons, ironing board covers, pipes, and cables; in saucepans and pans as a non-stick coating; in vascular prostheses and other implants; in dentistry as a barrier membrane for bone formation; it covers metal strings for guitars and other musical instruments; it coats the inside of valves, pipes, and containers.

Polyamides (PA) such as Nylon and Perlon: Are mainly used for textiles,

but also for parachutes, balloons, sails, ropes, fishing lines, for covering

tennis rackets, for strings of bowed and plucked instruments; for dowels, screws, housings, insulators, cable ties; for ladles, spoons, and other kitchen utensils; for Toothbrush bristles.

Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA): It is found, among other things, in shrink wraps, shower curtains, floor coverings, electric cables, adhesives, tufted carpets, shoe soles, as micropellets in cosmetic scrubs.

How dangerous are these substances for our health when they sneak into us as tiny synthetic creatures through the mouth, nose, and skin? Are the contaminants harmless in the end?

Increasing evidence of health hazards

The industry is busy researching plastics: composition, areas of application and purpose optimization, consumer needs, and market acceptance. Manufacturer studies on health hazards, on the other hand, are rare: the published ones give the all-clear; After all, customers only play along as long as they feel safe. Authorities are reluctant; governments hesitate, and independent scientists lack the money for the urgently needed research into risks and side effects.

However, the few results that are available so far effortlessly raise the alarm.

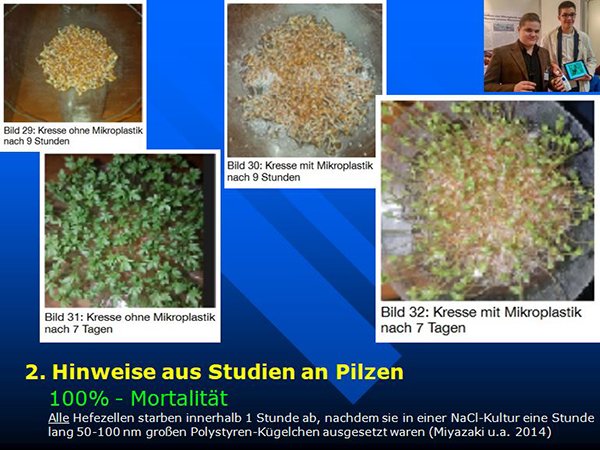

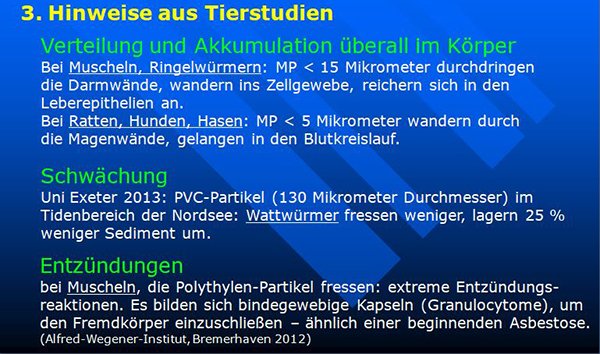

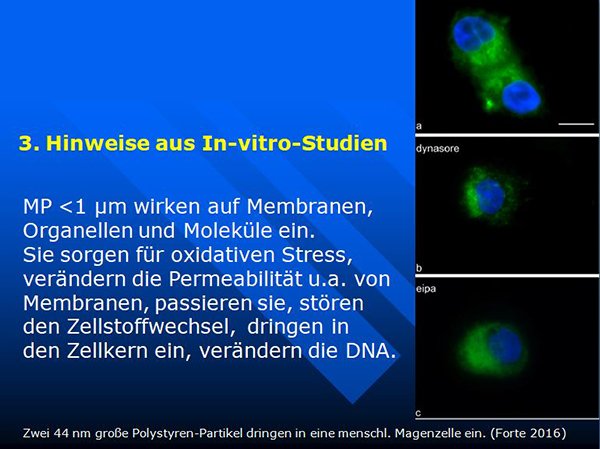

In experiments with mussels, oysters, and annelids, with rats, rabbits and dogs, several research groups found that particles smaller than five to 15 micrometers (10 to the power of -6 = 0.000001 m) can migrate through the digestive tract, the intestines, and penetrate stomach walls, lodge in lymph nodes, the brain, and other organs. The material accumulates in cell tissue, where it alters metabolism and causes inflammation.

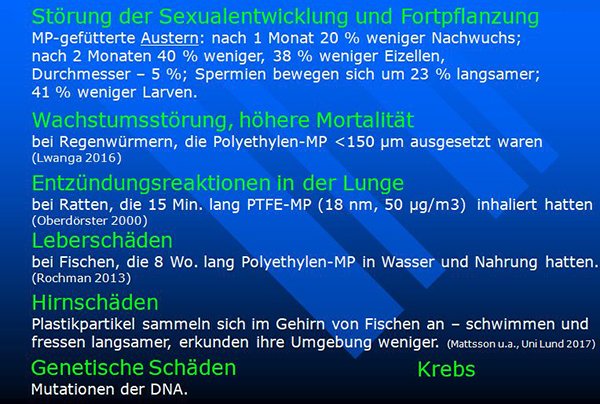

A group of researchers at the University of California in Davis found significant liver damage after just eight weeks in small fish that ingested the plastic bags and foiled polyethylene via water and food.

It was also found in fish, frogs, sea snails, and certain types of alligators: phthalates and polychlorinated biphenyls inhibit male sex hormones, reduce testosterone production, impair testicular function and lead to genital malformations.

French and Belgian biologists compared oysters that lived in clean water with oysters whose environment was contaminated with microplastic particles. In the first few weeks of the experiment, the latter had almost 20 percent fewer offspring. After two months, the minus had grown to around 40 percent, the number of egg cells had fallen by 38 percent, their diameter by 5 percent; the sperm moved 23 percent slower. 41 percent fewer larvae developed.

Marine biologists at the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Bremerhaven report similarly worrying observations after they fed tiny polyethylene particles to mussels in aquariums: “Within twelve hours, these particles accumulate in the stomach and in the liver epithelium, as well in a vacuoleous apparatus in the cell that we call ‘garbage can’; From there they are thrown out again into the surrounding body tissue, where they “trigger very extreme inflammatory reactions. Connective tissue capsules form to enclose these foreign bodies.” These pathological processes “remind us very much of what begins asbestosis in humans” – an incurable disease caused by asbestos fibers, which usually end fatally.

There is no question that people unwittingly ingest microplastics when eating contaminated meat. The amount can be impressive, as the biologist Liesbeth van Cauwenberghe from the University of Ghent calculates: “If you eat twelve oysters, you ingest about a hundred microplastic particles; the same applies to 250 grams of mussel meat. That doesn’t seem like much. But if you look at what Europeans eat in terms of shellfish per year, we estimate that a top consumer who eats a lot of shellfish ingests around 11,000 microplastic particles per year. That’s shocking.”

Does it make you sick too?

Because all previous studies on the biocompatibility of microplastics were only a few

For weeks, there has been a lack of solid scientific knowledge about the long-term health consequences of its consumption – in animals and even more so in humans. After all, observations of worrying connections have increased in the past decade. In September 2008, medical researchers from the University of Exeter caused a stir when they published a study on a representative cross-section of the US population, consisting of 1,455 adults between the ages of 18 and 74. The blood and urine samples revealed that the 25 percent with the highest levels of bisphenol A in the body were twice as likely to develop heart disease and diabetes as the 25 percent with the lowest BPA exposure.

An Australian team of researchers from the University of Adelaide found phthalates in 99.6 percent of all urine samples they took from 1,500 men over the age of 35. With higher concentrations of plastic, the likelihood of coronary disease, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure increases.

As previous studies have shown, high phthalate levels occur primarily in people who often eat plastic-packaged and industrially processed foods.

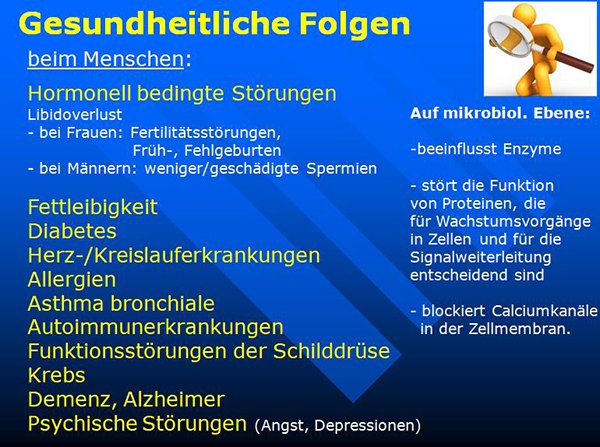

The list of health risks that doctors associate with plastic is getting longer and longer:

- Polyvinyl chloride (PVC): Cancer, birth defects, genetic changes, chronic bronchitis, ulcers, skin diseases, deafness, vision problems, digestive problems, and liver dysfunction.

- Phthalates: Hormonal disorders, asthma, developmental and reproductive disorders, cancer, birth defects, endometriosis, immune system disorders.

- Polycarbonate with bisphenol A: cancer, immunodeficiency, precocious puberty, obesity, diabetes, hyperactivity.

- Styrenes: Eye, nose, and throat irritation, drowsiness, unconsciousness, kidney, stomach, liver damage, red blood cell changes, lymphoma, leukemia.

- Polyethylene: cancer.

- Polyester: eye and respiratory tract irritation, skin rash.

- Formaldehyde: Cancer, birth defects, genetic changes, shortness of breath, headaches, skin conditions, fatigue.

- Polyurethane: bronchitis, skin, eye, and lung problems.

- Acrylic: Difficulty breathing, nausea with vomiting, diarrhea, headache, exhaustion.

- Tetrafluoroethylene: Eye, nose, and throat irritation, breathing difficulties.

Experimental research on humans has so far not been carried out – but what should it look like? Do we want to inject suspected toxic substances into subjects for test purposes to observe how they become terminally ill with interest? Plastic pollution can only be examined afterwards. Even if it then turns out that it is associated with specific health problems, a causal connection can never be proven. Skeptics are always reassuring, pointing to possible other disease-causing factors

One of the routine trivializers is the Federal Institute for Risk of all people assessment (BfR). The same government agency was recently caught copying a safety report from glyphosate manufacturer Monsanto. “According to the current state of knowledge, a health risk for consumers is unlikely,” she said in a 2014 statement that has not been updated to date. It’s still too early to make any assessments of the possible health hazards posed by microplastics; she explains – a twisted form of trivialization. As long as no money flows into research, there can be no research results that allow a well-founded risk assessment.

At least it seems clear that most plastics also have an effect on the human body.

“endocrine disruptors” – disrupt hormone balance because their structure mimics estrogen. Phthalates and polyethylene most likely promote hormone-related tumor diseases such as breast, prostate, and testicular cancer, obesity and type 2 diabetes, reduced sperm quality, endometriosis, precocious puberty, and malformations the reproductive organs, as even the US Environmental Protection Agency recently acknowledged. The styrene contained in polystyrene is considered carcinogenic.

Plastic bottles as a mass poisoner

One of the most insidious sources of plastic toxins is beverage containers. Three out of four mineral water bottles that we buy from manufacturers are no longer made of glass but conveniently made of plastic, primarily PET. How practical, convenient, and easy for us to carry around, especially throwing away. However, highly toxic chemicals are released from the plastic covers, especially bisphenol A and acetaldehyde, plasticizers such as DEHP, the structurally similar DEHF (diethyl hexyl fumarate), and phthalates. This “leaching” is dependent on time and heat: the longer a liquid is in the plastic packaging, the more it transfers. The amount of poison escaping increases with temperature. The warmer they get, the longer food has contact with them; the more plastic components are transferred to them. Anyone who has ever left a plastic water bottle in the car in the summer heat and then drank from it knows that this liquid tastes strangely chemical. Acetaldehyde released by the plastic ensures this.

Whoever uses it to quench their thirst is ignoring the current state of research. BPA was found in nine out of ten urine samples provided by 190 men with fertility problems; Among other things, a 23 percent lower seed concentration and around 10 percent more DNA damage was found in those with exceptionally high BPA concentrations. Sexual dysfunction was particularly noticeable in factory workers exposed to bisphenol A on an ongoing basis. New studies point to links between an increased level of BPA in the blood and diabetes, cardiovascular problems, lack of libido, and obesity. In addition, physicians found connections between early exposure to bisphenol A and anxiety, depression, and ADHD in adolescents. BPA may also be involved in thyroid dysfunction, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and other autoimmune diseases, dementia and Alzheimer’s, miscarriages, and breast cancer. It is also suspected of interfering with the formation of tooth enamel (“molar incisive hypomineralization,” MIH). It impairs the function of crucial proteins for cell growth processes and thus promotes tumor development. Bisphenol A also has hormone-like effects: it disrupts sexual and brain development in laboratory animals. After bisphenol A administration, male mice switched to female behaviors, after which conspecifics avoided them.

Many consumers are put off by advertisements for “Bisphenol-A-free” plastic bottles impress. However, an American research team also found estrogen-like substances in the new substitute material Tritan. No one knows what other long-term effects they will have.

“Ticking Time Bomb”

Not only the microplastic particles themselves are toxic but also those in the water floating pollutants that dock with them: including traces of fire retardants, agricultural pesticides, abrasion from biocidal paints, drug residues, organic chlorine compounds, heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, chromium, arsenic, zinc, mercury and nickel. Many microorganisms also colonize the plastic surface. Among them, the microbiologist Gunnar Gerdts from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) found many pathogens – such as the bacterium Vibrio parahaemolyticus, which can cause gastrointestinal inflammation and vomiting diarrhea. “Who knows,” he says, “perhaps the large quantities of microplastics in the sea will contribute to the spread of diseases in the future.” If plastic particles get into our organism, they often have such stowaways in their luggage. Many are suspected of being carcinogenic or hormonally active.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers are investigating the ability of microparticles to bind other substances used to release drugs in the body with a time delay. The plastic particles, they assure, would then be excreted again. How do you know?

In short, microplastics are “a ticking time bomb,” warns Rolf Buschmann from the Bund für Umwelt- und Naturschutz (BUND). “In the worst case, we’ll have to live with this stuff for a few hundred years,” says Oldenburg biochemist Gerd Liebezeit.

Deny, downplay, stall

Voluntary commitments by the industry, on which the federal government is naively relying, as in the diesel scandal, make a mockery of the seriousness of the situation. Should it be left to a garbage thrower to decide at its own discretion whether to continue? Especially as one who pretends there is no problem? “After a thorough examination of the situation,” the leading association of the life economy (BLL) is blind and deaf, “a causal connection between potential microparticles in individual foods and plastic particles released by cosmetics or textiles is not apparent to us. It can be ruled out that particles from bodies of water and seas get into the groundwater and consequently via the drinking water into food processing or the food chain.” If necessary, they, like the German Brewers’ Association, launch counter-reports that they “prove” that their product is harmless – without disclosing which research methods were used.

The federal government, ministries, and help with denial downplaying, delaying

Control authorities scandalously with. When asked about the Orb Media study, the Federal Environment Agency said the findings were “not worrying,” a few plastic particles per liter, “very little – that doesn’t mean anything, that’s background noise.” A health hazard is “very unlikely.” How can a public health agency look at the concentration of a single group of substances in isolation? The minor amounts of different origins can add up enormously – not to mention their unexplored interactions with each other.

At the end of 2016, in response to a question from the “Greens” about microplastics in cosmetics, the federal government briefly referred to the obligation to label ingredients on the packaging – as if the average consumer knew what to do with the chemical nomenclature there and draw the correct conclusions. However, the federal government has “no knowledge” about “consumer knowledge regarding the use and effects of microplastics.” Both the Federal Environment Ministry and the Federal Ministry of Food stated in response to a journalist’s request that they were not responsible for the problem of microplastics in brewing water – and each referred to the other department.

Massive protests and consumer abandonment, accompanied by business-damaging media echoes, impress the industry considerably more than so many alarming studies – because they directly threaten their profits. Sometimes they rethink amazingly quickly: companies such as Unilever, Body Shop, Johnson & Johnson, and Procter & Gamble announced as early as 2013 that they would completely ban plastic from their products “in the near future.” The manufacturer AOK has already replaced microplastics in its peeling product with silica, a type of sand, just like Elmex in its toothpaste. After all.

Nevertheless, control is better than trust: As early as October 2015, the Cosmetics Europe industry association members solemnly committed themselves to quickly phasing out microplastics from their products. Nevertheless, in early 2017, Öko-Test found them in most of the 22 body scrubs examined. A BUND list as of July 2017 shows how widespread plastic is in personal care products. Code check, the most extensive German-language online consumer guide, summed up the promises that were kept as “not much to remember” after comparing almost 103,000 cosmetic products from 2014 and 2016. In many products, the use of polyethylene has even increased slightly.

Only at the end of 2017, more than a quarter of a century after scientists’ first urgent warnings, the Federal Environment Agency recommended the EU Commission for a Europe-wide ban on microplastics – curiously enough, limited to the use of solid particles in cosmetics. No mention of all other application areas, liquid, gel, or wax-like plastics.

Since Connecticut and California are long further, in 2015, both states enacted a sweeping ban that included questionable substitutes as a precaution.

And elsewhere? As is usually the case when economic interests are at stake, government agencies provide outrageous assistance in shifting the burden of proof: “As long as it is not beyond doubt that a product is dangerous,” the motto goes, “it stays on the market.” who prefer to protect their people than powerful corporations, does not apply the other way around: “As long as justified doubts about the harmlessness of a product have not been completely dispelled, it has no place in our living environment”? Not letting legitimate concerns talk you out may look “anti-innovation.” Still, it is smart and responsible – with plastics no less than with pesticides, genetically modified organisms, nanomaterials, radiation sources, and pharmaceuticals.

The legal framework in which chemical substances are evaluated and approved continues to open the floodgates to poisoning citizens and the environment. In 2007, from Lisbon to Athens, REACH (Regulation 1907/2006) came into force: the European Chemicals Regulation, which “is intended to ensure a high level of protection for human health and the environment,” as the Federal Environment Agency assures. What exactly is this protection? Thanks to REACH, it is no longer enough for manufacturers to merely register their new substances – no, now they also have to “submit data” and “assess the risks themselves.” Self? As a matter of fact. The Helsinki European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) only checks what you submit for formal “completeness.” If, based on the documents submitted, the authority exceptionally classifies certain substances as “particularly alarming” – for example, because they are carcinogenic, mutagenic, toxic to reproduction, accumulate in organisms, or have a hormonal effect – this does not lead to their own studies and controls, to bans and public warnings, but only to “restrict” and “time limit” the areas of application. Lobbyists in Brussels have once again done a great job.

What consumers can do?

How do we get rid of plastic pollution? Naturopathy knows elimination processes for all kinds of pollutants – it also seems largely powerless against plastic. Whether an “anti-plastic tea” made from mullein and olive leaves, lemon balm, and fenugreek seeds will help, as a couple of healers from Upper Bavaria promise, awaits proof. In Internet forums, some non-medical practitioners recommend “regular saunas and sweating,” the amino acid glycine as a plastic binder, fatty acids with the highest possible omega-3 content, liver and bile support, and binding agents in the intestine. Efficacy studies are pending.

What is the advice for consumers in this tricky situation? At least he largely escapes the microplastics in drinking water: Instead of lugging crates of PET bottles home from the supermarket, he better turns on the domestic water tap. Its tap water is far better controlled than the beverage industry’s bottled thirst-quenchers, and it’s cheaper. If he wants even more security, he buys a high-quality filter system.

Otherwise, all he can do is set a good example: Fewer fibers are lost.

Clothing when washed for shorter periods, at lower temperatures, and lower spin speeds. Organic supermarkets and health food stores offer environmentally friendly alternatives to plastic cosmetics. We should clean paint brushes in buckets whose contents belong to a collection point for hazardous waste.

In addition, each of us can help a little with environmental protection and self-protection. Let’s make our household as plastic-free as possible. Let’s avoid elaborately packaged goods, plastic bags, plastic containers, shrink-wrapped fruit, and vegetables. We prefer reusable glass packaging. Let’s not expose our children to pacifiers, toys, water bottles, and plastic food containers. If we do without body care with microplastic beads, we use natural cosmetics; in certified organic skin cleansers, for example, scrub crushed nutshells, fruit kernels, finely crushed volcanic rock, salts, ground apricot or grape seeds, almond bran, healing earth or

Silicic acid dead skin cells from the body. Suppose we use liquid detergent instead of powder. In that case, we wash as briefly as possible, at the lowest possible temperature, with a few revolutions as possible – then not as many fibers are washed out. Let’s never empty the lint filter of the washing machine and dryer down the drain. We do not use microfiber cleaning cloths. When buying clothes, if we prefer natural fibers such as cotton, wool, silk, and linen, which can degrade, we avoid polyester, acrylic, nylon, GoreTex, and similar synthetic fibers. There are durable alternatives made of wood and metal to disposable razors. We prefer stores that offer unpackaged products. Let’s separate and collect our rubbish carefully. Let’s only leave our apartment with a cloth bag in our handbag or briefcase. Let’s only drink coffee to go from the glass or ceramic mug we’ve brought with us. Let’s reach for grandma’s old-fashioned wooden cooking spoons and spatulas. Let’s replace cling film, plastic bags, and plastic cans with screw-top jars, and Tupperware cans with lunch boxes made of stainless steel and glass. Let’s support parties and initiatives that actively tackle the problem instead of just making words.

The plastic age has made us unsuspecting guinea pigs of a unique, uncontrolled global experiment: how much can our planet, particularly our organism, withstand constant infusions of poison in mini-doses? “Our indifference alone created the plastic problem,” explains the Bengali economist Muhammad Yunus, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 as the founder of the microcredit idea. “What is needed now is a firm determination to get rid of it – before it gets rid of us.”

by Dr.Harald Wiesendanger– Klartext

Support “Ways Out Charity“! With your support, we can help and move forward. > https://bit.ly/3wuNgdO

Editors Note > ‘We’re All Plastic People Now’: A Groundbreaking Documentary.

Sources

Kanishka Bhunia u.a.: „Migration of Chemical Compounds from Packaging Polymers during Microwave, Conventional Heat Treatment, and Storage“ (Migration chemischer Verbindungen aus Verpackungspolymeren während der Mikrowellenbehandlung, der konventionellen Wärmebehandlung und Lagerung), Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 12 (5) 2013, S. 523-545, DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12028,

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1541-4337.12028/abstract#

Werner Boote: Plastic Planet, Dokumentarfilm, USA 2013, 95 Min., Trailer:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=mlgmG4OrdyU

BUND: Mikroplastik – Die unsichtbare Gefahr. Der BUND-Einkaufsratgeber, Berlin 2017,

www.bund.net/fileadmin/user_upload_bund/publikationen/meer/meere_mikroplastik_einkaufsfuehrer.pdf

BUND: Mikroplastik-Studie 2016 – Codecheck-Studie zu Mikroplastik in Kosmetika,

http://corporate.codecheck.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Codecheck_Mikroplastikstudie_2016.pdf.

Bundesanstalt für Risikobewertung (BfR): „Fragen und Antworten zu Mikroplastik“, FAQ des BfR vom 1. Dezember 2014, www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/fragen-und-antworten-zu-mikroplastik.pdf

Lisbeth van Cauwenberghe/Colin Janssen: „Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption“ (Mikroplastik in Muscheln für den menschlichen Verzehr), Environmental Pollution 193/2014, S. 65-70; DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2014.06.010; als PDF: www.expeditionmed.eu/fr/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Van-Cauwenberghe-2014-microplastics-in-cultured-shellfish1.pdf.

Ecology Center: „Adverse Health Effects of Plastics“ (Schädliche Auswirkungen von Kunststoffen auf die Gesundheit), o.J., https://ecologycenter.org/factsheets/adverse-health-effects-of-plastics/

D. Gentilcore u.a.: „Bisphenol A interferes with thyroid specific gene expression“ (Bisphenol A stört die schilddrüsenspezifische Genexpression), Toxicology 304/2013, S. 21-31

Gunnar Gerdts/Lars Gutow: „Die Suche nach dem Mikroplastik“, zuletzt aktualisiert am 21.2.2017, https://www.awi.de/im-fokus/muell-im-meer/mikroplastik.html

Roland Geyer u.a.: „Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made“ (Herstellung, Einsatz und Schicksal von sämtlichem Plastik, das jemals produziert wurde), Science Advances 3 (7) 2017, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782, http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/7/e1700782.full.

Johannes Kaiser: „Mikroplastik: Gefährlich, unsichtbar und unerforscht“, Deutschlandfunk Kultur – Zeitfragen, 30.10.2014, www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/mikroplastik-gefaehrlich-unsichtbar-und-

unerforscht.976.de.html?dram:article_id=300248.

Datis Kharrazian: „The Effect of Plastic Products on Autoimmune Disease and Thyroid Function“ (Die Wirkung von Kunststofferzeugnissen auf Autoimmunerkrankungen und Schilddrüsenfunktion), Dr.K.News 27.7.2014, https://drknews.com/effect-plastic-products-autoimmune-disease-thyroid-function-stop-using-plastic-coffee-lids/

Kai Pohlmann: „Das Mikroplastik, das aus der Waschmaschine kommt“, Deutsche Meeresstiftung, 25.5.2016, www.meeresstiftung.de/das-mikroplastik-das-aus-der-waschmaschine-kommt

Chris Tyree/Dan Morrison: Invisibles – The plastic inside us (Die Unsichtbaren – Das Plastik in uns), https://orbmedia.org/stories/Invisibles_plastics

Medical News Today, 14.7.2017: „Common chemicals in plastic linked to chronic disease“ (Häufige chemische Substanzen in Kunststoffen, die mit chronischen Krankheiten in Verbindung gebracht werden), https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318422.php

John D. Meeker u.a.: „Semen quality and sperm DNA damage in relation to urinary bisphenol A among men from an infertility clinic“ (Samenqualität und DNA-Schäden an Spermien im Zusammenhang mit Bisphenol A im Urin bei Männern aus einer Unfruchtbarkeitsklinik), Reproductive Toxicology 30 (4) 2010, S. 532–539, doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.005.

John D. Meeker/K.K. Ferguson: „Relationship between urinary phthalate and bisphenol A concentrations and serum thyroid measures in U.S. adults and adolescents from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2008“ (Zusammenhang zwischen Phthalat- und Bisphenol-A-Konzentrationen im Urin und Serum-Schilddrüsenwerten bei US-amerikanischen Erwachsenen und Jugendlichen aus der nationalen Gesundheits- und Ernährungsuntersuchung (NHANES) 2007-2008), Environmental Health Perspectives 119 (10) 2011, S. 1396-402, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3230451/

Nadia von Moos u.a.: „Uptake and Effects of Microplastics on Cells and Tissue of the Blue Mussel Mytilus edulis L. after an Experimental Exposure“ (Aufnahme und Wirkung von Mikroplastik auf Zellen und Gewebe der Blaumuschel Mytilus edulis L. nach experimenteller Exposition), Environmental Science & Technology 46 (20) 2012, S. 11327–11335, DOI: 10.1021/es5302332w

Reuters, 16.9.2008: „Common plastics chemical linked to human diseases“ (Wie weitverbreitete Kunststoffe mit menschlichen Erkrankungen zusammenhängen), www.reuters.com/article/us-chemical-heart/common-plastics-chemical-linked-to-human-diseases-idUSLF18683220080916

Chelsea M. Rochman u.a.: „Ingested plastic transfers hazardous chemicals to fish and induces hepatic stress“ (Verschluckter Kunststoff überträgt gefährliche Chemikalien auf Fische und stresst die Leber), Scientific Reports 3/2013, doi:10.1038/srep03263, https://www.nature.com/articles/srep03263.

Neda Smith/Patrick Lovegrove: „How Plastic Makes Your Brain Sick“ (Wie Plastik dein Gehirn krank macht), www.bewellbuzz.com/journalist-buzz/mental-illness-plastic-byproducts-connection-may-make-brain-sick/

Rossana Sussarellu u.a.: „Oyster reproduction is affected by exposure to polystyrene microplastics“ (Polystyrol-Mikroplastik beeinträchtigt die Fortpflanzung von Austern), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (9) 2015, S. 2430-2435, www.pnas.org/content/113/9/2430.abstract

US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): „Toxilogical Threats of Plastic“ (Toxikologische Bedrohungen aus Kunststoff), Update 2017, www.epa.gov/trash-free-waters/toxicological-threats-plastic

Umweltbundesamt (Hrsg.): Bisphenol A – Massenchemikalie mit unerwünschten Nebenwirkungen (PDF; 522 kB), Dessau-Rosslau, Juli 2010; CHEM Trust publications on obesity and diabetes, Stand: 2012.

University of Missouri, 27.6.2011: „BPA-Exposed Male Deer Mice are Demasculinized and Undesirable to Females“ (Männliche Hirschmäuse, die BPA ausgesetzt sind, werden unmännlich und von Weibchen gemieden), http://munews.missouri.edu/news-releases/2011/0627-bpa-exposed-male-deer-mice-are-demasculinized-and-undesirable-to-females-new-mu-study-finds